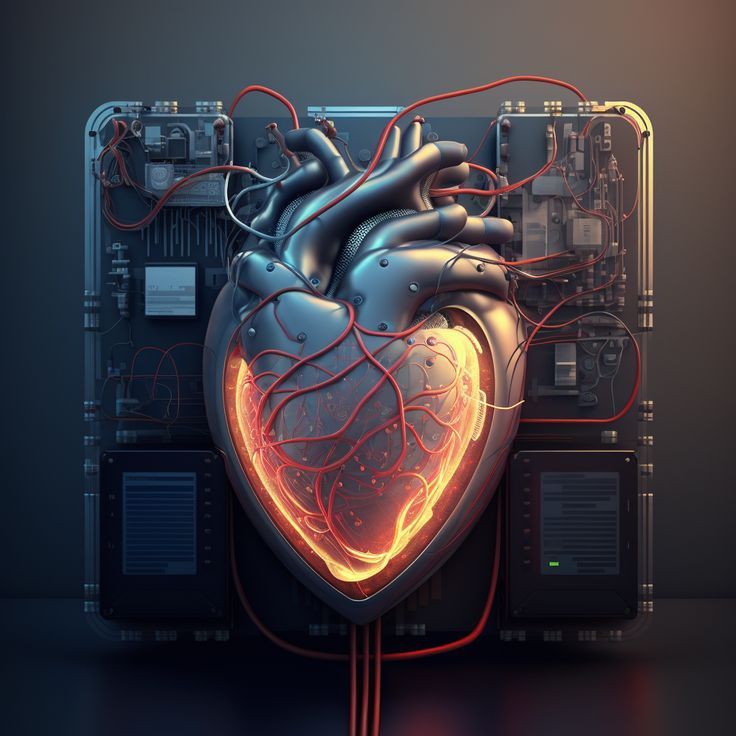

Future technological advancements may not only grant us capabilities surpassing human physiology but also blur the boundaries between machines and humans. Cyborgs—these perfect fusions of humanity and machinery—could become an integral part of our era. So, as this fusion of biology and technology progresses, if our bodies are modified with artificial intelligence-enabled “mechanical organs,” can traditional insurance still provide coverage? This is a question brimming with imagination and challenges.

In this era of rapid technological advancement, the concept of cyborgs is no longer confined to science fiction films. Whether it's implanting vision-enhancing eyes or replacing limbs with prosthetics, an increasing number of “mechanical organs” are carving out a place in human life. These modifications not only significantly enhance individual physical capabilities but also offer more effective treatments for those requiring physiological replacements. Yet as these organs grow increasingly technological and approach artificial intelligence, shouldn't they also be covered by corresponding protections?

First, let's examine the traditional definition of insurance. Insurance typically provides compensation for potential losses in areas like health and property. But if your body no longer falls entirely within the realm of a “natural person,” can insurance still cover these ‘mechanical’ components? Currently, many insurance companies are exploring new coverage models. For instance, as implantable devices and artificial organs become more common, numerous health insurance plans are beginning to include certain “high-tech” medical devices within their coverage scope.

However, the “mechanical organs” involved in cyborgs extend beyond simple medical devices. They may possess self-repair capabilities or even upgrade through artificial intelligence. In such cases, traditional insurance models may prove inadequate. Coverage must extend beyond biological damage to address “intelligent risks”—such as potential hazards from AI system failures, cyberattacks, or programming errors.

Second, cyborg insurance raises complex ethical and legal questions. If a cyborg's limb malfunctions or sustains damage, who bears responsibility? The manufacturer? Or the individual? Should an insurance company cover losses from a hacked “mechanical organ”? Resolving these issues requires collaboration among legal, ethical, and technological experts.

Moreover, the high autonomy of artificial intelligence and mechanical organs presents challenges for future insurance product innovation. Can insurers assess these highly personalized risks? For instance, can AI perceive risks like humans, and does it possess predictive and decision-making capabilities? If AI grants cyborgs extraordinary physical functions but defects or vulnerabilities lead to harm, how should insurers define the boundaries between “accident” and “liability”?

Perhaps the future insurance market will develop products specifically tailored for cyborgs. Such insurance would extend beyond physiological coverage to encompass technological risks, including scenarios like “AI malfunction” or “mechanical organ damage.” The fusion of humans and technology may give rise to an entirely new form of insurance—one that safeguards both individual physical well-being and the stable operation of technological products.

In short, the advent of the cyborg era will not only transform human lifestyles but also redefine the very concept of “insurance.” In that era, insurance will no longer merely provide coverage for biological entities but will offer comprehensive protection for these “new life forms” that bridge the gap between biology and machinery. Though all this may seem distant today, the rapid pace of technological advancement suggests this era may not be far off.